![bagh-cave-madhya-pradesh]()

The forest was denser… life expressing itself unhindered had covered the abandoned rock cut caves. The caves were formerly said to be inhabited by Buddhists. Tigers (Bagh) chanced upon them in their wanderlust. They had found a home that had beautiful Buddhist mural paintings adorning the walls in addition to the cool, shaded refuge from the world outside…Villages around the area started referring to the caves as the tigers’ home. And they came to be called Bagh Caves.

The Khatris are a community whose inward beings dance the Sufi way. They came under the influence of a sufi man and it stuck a long lasting chord. Originally Ajrakh printers they ventured into places to sell their fabrics and their enterprising ways kept them upfloat. From Larkana in Sind (today’s Pakistan) to Pali, to the Marwadi Thar, to Manawar in Madhya Pradesh, their journey came to a stop and they settled down in Bagh in 1962 as they saw their grandfather and uncles returning back to their ancestral land (Karachi, Pakistan) during Partition.

![Manavar]()

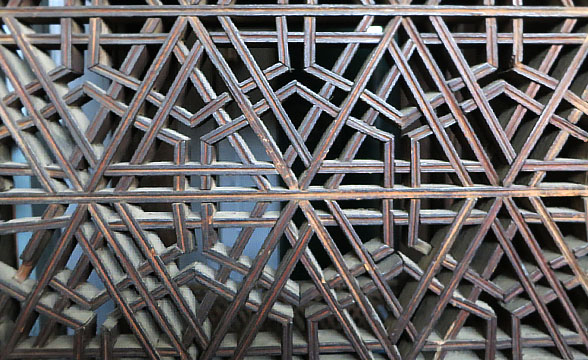

They discovered something that was seminal to their work and their lives. The river of the area, Baghini, was special. It’s copper content was high and that would account for all the beautiful deep colors in the fabrics that would be offered from the region. Also, the flowing water would contribute essentially to the dyeing process. Innovations made way and the printing flourished. Block designs were instrumental to the innovation. Of the paintings of the Bagh caves and that of Taj Mahal, they spoke. The base fabrics were experimented with. Vegetable dyes were adhered to.

![bagh-prints-motif]()

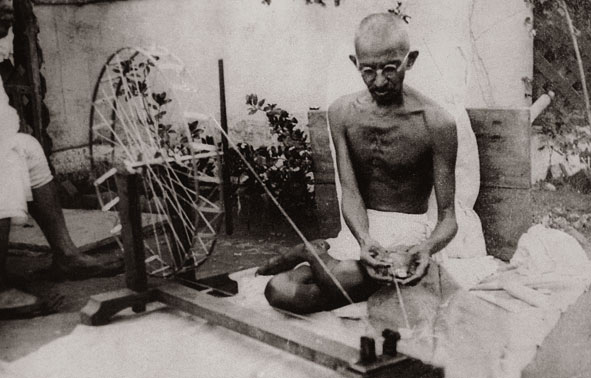

Some of the traditional motifs used are ‘Nandana’ mango motif, ‘Tendu’ plant motif, ‘Mung Ki Phali’ motif, ‘Khirali Keri’ motif, ‘Leheria’ motif, ‘Jowaria’ motif and the ‘Phool Buta’ motif. This craft gives great

flexibility for developing innumerable surface designs through permutations and combinations of borders, ‘Buti’(motif) and ‘Jaal’ (floral net) blocks.

An elaborate process of printing and dyeing gives birth to the fine craft of ‘Bagh’. With wooden blocks made taking inspiration from the alluring fauna and architecture for printing, many traditional and contemporary patterns are passed onto cloth using natural dyes. Also called ‘Thappa Chappai’ (Thappa means Blocks, Chappai means printing) or ‘Alizarine print’ since ‘Alizarine’ gives it its characteristic red color Bagh has come a long way from its formative years.

![fabric-for-bagh-printing]()

The raw materials involved are base fabrics of cotton or silk, natural dyes and wooden blocks.Cotton is readily available from the nearby markets of Indore. Alternatively, silk-by-cotton fabric is purchased from the towns of ‘Maheshwar’ and ‘Chanderi’. ‘Cambric’ cloth is purchased from Mumbai to make dress materials while ‘Mulmul’ fabric comes from ‘Bhivandi’ town. Again, Silk cloth materials like ‘georgette’, ‘crepe’ and ‘chiffon’ are procured from Indore and Mumbai. ‘Tussar’ silk is procured from the towns of ‘Raigarh’ and ‘Bhopal’. Finally, ‘Dhaka Jute’ is purchased from Delhi.

![bagh-process-1]()

Raw material processing is carried out in copper tubs. The fabric is washed to get rid of the impurities and left to dry in the sun. Once dry, it is dipped in a solution made of castor oil and goat droppings, which react with each other to generate heat and this makes the fiber absorbent. The cloth is dipped in this solution repeatedly and trampled on by foot to produce froth and then left to dry. After this, it is soaked in a starch solution of ‘Tarohar’ and ‘Harada’ powder and sun dried again. This also gives the fabric its yellow tone. It is necessary to dry it in the shade to prevent the desired yellow color from turning green due to the sun.

![imli-seed-for-printing]()

A paste is made by mixing the dye with ‘Dhavda’ (a kind of flower) gum. There are two types of pastes: one is a red in color and the other is black. For the printing of red color, alum is boiled in a solution along with Tamarind seeds to create a paste. For black, Iron rust is boiled till it becomes a thick paste and this is used to print black. After preparing the pastes, they are filtered and poured into wooden trays. This dye is applied to the wooden block by pressing the block onto the tray.

![bagh-block-printing-process]()

Meanwhile, the yellowish cloth obtained from the earlier process is evenly stretched across the table. A black boundary is drawn with plain stamps around the cloth. The cloth now becomes a canvas for the craftsman who skillfully prints and matched the intricate designs. He starts printing in rectangles, beginning from the outer portion of the cloth and moving inwards until it is covered. He avoids overlapping of the prints by putting an old cloth or paper where the printing has already been done. It is left to dry and washed once more.

![bagh-printing-process]()

For the ‘Bagh’ printed cloth to have its characteristic contrast and finishing, it must pass through another dyeing process. ‘Alizarin’ mixed with ‘Dhavadi’ flower extracts are boiled together in a big copper container concealed in a cement structure. The printed cloth is then left to boil in it for five to six hours. The printed dye containing alum reacts with Alizarin to produce red. At the same time, ‘Dhavadi’ flowers work like a bleaching agent on portions printed with ‘Harada’, creating white areas. After this process, through which the designs turn red, black and white, the cloth is left to sundry in shade.

The printed dry fabrics are finally taken to Baghini River for subsequent washes. The iron content of the river and the running water helps in bringing out finer colors and also softens the fabric. Though for all the previous stages, the artisans use the water stored in in-house tanks.

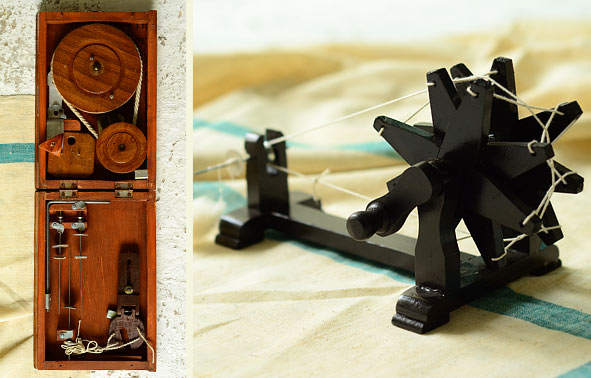

![bagh-blocks]()

The craftsmen only use teak wood, locally known as ‘Sagwan’, sourced from Valsad, a town near Gujarat-Maharashtra border for making Bagh printing Blocks. Teak provides the perfect base for carving intricate motifs as it is a dense and strong wood. It doesn’t absorb water or distort in shape even after years of usage. The craftsmen use a hand-drill arrangement that involves a bow called ‘Kamthi’ and a driller ‘Saarardi, to drill out larger portions of the design voids from the block. For finer carving and finishes they use a variety of chisels of varying shapes and sizes. These tools are also handmade by them according to their requirements. Once prepared, the blocks are immersed in oil for a few days to protect them against warping and insect attacks. This is important since the block is going to be in constant touch with water-based dyes, which make them more vulnerable to decay. Wooden blocks range from as small as an inch to as large as sixteen inches in size. While a basic block (3’ to 4’ across) takes a day or two to be made today, an intricate one may take almost a week’s work.

![Bagh-craftsmen]()

The local Adivasi community that practiced the block printing technique lacked sustenance and Ismail Khatri played an important role in their revival.Today, Bagh sustains more than 2500 artisans and also the craft is a matter of joy and astonishment to all those it reaches to. From Lehengas and Ghaghras, to sarees, salwars and dupattas, to skirts and shirts, to bedcovers and curtains, lampshades and scarves, kerchiefs and wall pieces; adaptation to the world about, has secured it’s survival. A name is a symbol. It represents something. The tiger, oblivious to it’s place and position in the human world, has lent it’s name to this human endeavour, which is not just the palpable final object, but the human spirit that is essentially the tiger’s spirit as well.